Dawoud Bey: An American Project Opens at the MFAH in March 2022

Houston will host this major retrospective of the preeminent photographer with MFAH featuring Bey’s most recent work

The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, will host Dawoud Bey: An American Project, a retrospective of the influential photographer’s career. Co-organized by the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and the Whitney Museum of American Art, the exhibition will be on view at the MFAH through May 30, 2022.

Bey (b. 1953) has dedicated more than four decades to portraying underrepresented communities and histories. From portraits in Harlem to nocturnal landscapes, classic street photography to large-scale studio portraits, his works combine an ethical imperative with an unparalleled mastery of his medium. Featuring approximately 85 works, the exhibition spans the breadth of Bey’s career, from the 1970s to the present. Organized both thematically and chronologically, it ranges from his earliest street portraits in Harlem (1975–78) to his most recent historical explorations, of the Underground Railroad (2017) and, unique to the Houston presentation, of Louisiana plantations (2020).

“Dawoud Bey is one of the preeminent photographers of our day,” said Gary Tinterow, Director and Margaret Alkek Williams Chair, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. “As the exhibition’s co-curators have so aptly noted, the exhibition and its evocative title introduce Bey’s deeply humanistic photographs into a long-running conversation about what it means to represent America with a camera.”

Bey received his first camera as a gift from his godmother in 1968, when he was 15. The following year, he saw the landmark, and highly divisive, exhibition Harlem on My Mind at The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. The exhibition, widely criticized for its failure to include significant numbers of artworks by African Americans, nonetheless made an impression on Bey and inspired him to take up his own documentary project about Harlem, in 1975. Since that time, Bey has worked primarily in portraiture, making tender, psychologically rich and direct portrayals of black subjects and rendering African-American history in a form that is poetic, poignant and immediate.

The exhibition includes work from nine major series and is organized to reflect the development of Bey’s vision over the course of his career, as well as his prolonged engagement with certain themes over time.

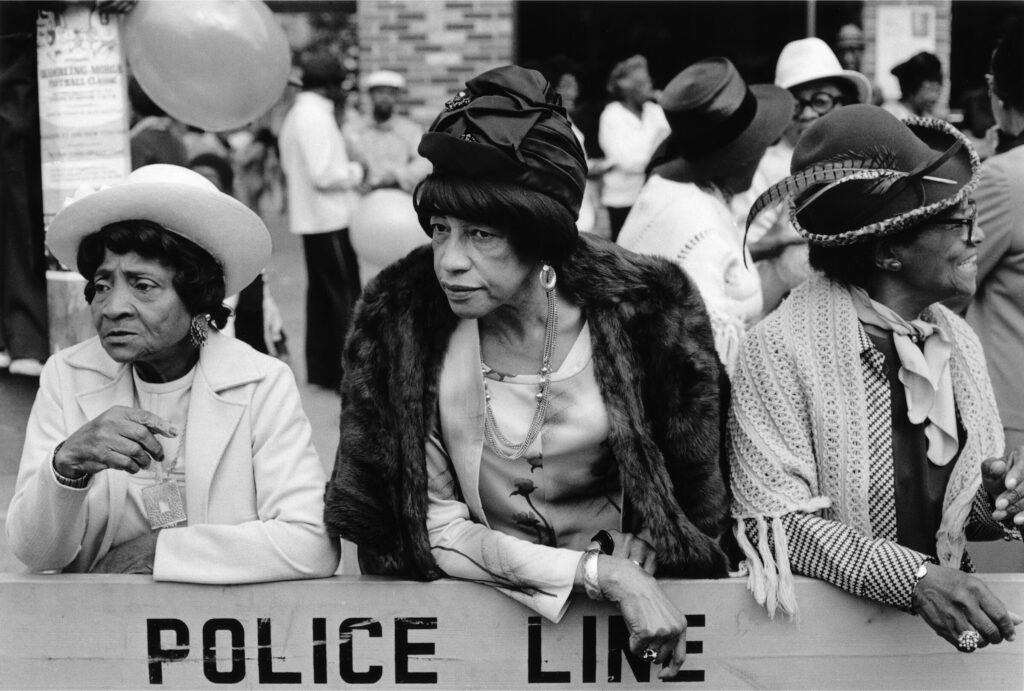

THE STREET A landmark black-and-white series created from 1975 to 1978, Harlem, U.S.A. documents portraits and street scenes with locals of this historic neighborhood. As a young man growing up in Queens, Bey was intrigued by his family’s history in Harlem—his parents met in church there and it was home to many family and friends he visited throughout childhood. Bey describes the experience of creating Harlem, U.S.A. as a sort of homecoming. This series premiered at the Studio Museum in Harlem in 1979 when the artist was just 26.

The exhibition also includes a powerful series of street photographs Bey made in Syracuse, New York, demonstrating not only his keen eye for portraiture and the spontaneous choreography in the streets, but also his sensitivity to his subjects’ environment. In the 1980s, Bey moved from the easily portable 35mm camera he used to photograph Harlem, U.S.A., to a heavier, more conspicuous, large format (4 x 5”) camera and Polaroid Type 55 film to create a series of more formal “street portraits” in cities such as Brooklyn, New York, and Washington, DC. With new equipment and a new approach, Bey began to engage his subjects more deliberately, creating work that elicits an intimate exchange between photographer and subject and, by extension, with the viewer.

The series Harlem Redux marks Bey’s return to photograph the Harlem community during 2014–2017, almost 40 years after his original series. Unlike the black-and-white pictures of Harlem, U.S.A., the new series comprises large-format color landscapes and streetscapes that mourn the transformation of the celebrated African-American community as it becomes more gentrified and its original residents are increasingly displaced.

THE STUDIO From the street Bey moved into the studio, using a massive 20 x 24” Polaroid camera to make a series of sensitive and direct color portraits first of friends, then later of teenagers he met through a residency at the Addison Gallery of American Art in Andover, Massachusetts. At this time, Bey also began experimenting with beautifully lit and framed multi-panel Polaroid portraits, inspired in part by an interest in challenging the singularity of the photographic print. Bey’s work at the Addison Gallery led to another residency, at the University of Chicago’s Smart Museum. There, he began a series he would call Class Pictures, creating striking, large-scale color portraits of high-school students accompanied by text that he invited his subjects to contribute. Seeing this kind of collaboration and community building as a key part of his practice, Bey views the conversational and attitudinal shifts that result from this process of exchange as integral to the work as the final objects themselves. Bey continued Class Pictures with high schools across the United States between 2003 and 2006. Focusing on teenagers from a wide range of economic, social and ethnic backgrounds, he created a diverse group of portraits that challenges teenage stereotypes.

HISTORY Three of Bey’s more recent projects explore aspects of African-American history in a form at once expressive and immediate. The Birmingham Project, created in 2012 as a commission from the Birmingham Museum of Art, memorializes the victims of the 1963 bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama, and its violent aftermath. Expressive portraits of girls and boys who are the ages of the bombing victims are paired with photographs of adults who are the ages that those children would have been in 2012. As Keller and Sherman write in their introduction to the exhibition catalogue, “Each diptych represents what was lost and what could have been, charging sitter and viewer alike with the heavy burden of bearing witness.” Half of this series was made in Birmingham’s Bethel Baptist Church, which served as the original headquarters for the Alabama Christian Movement for Human Rights during the civil rights movement. The other half was made in the Birmingham Museum of Art, which commissioned the project as part of a citywide effort to commemorate the lives lost on September 15, 1963.

Along with the portraits, Bey created a single-channel video shot in locations throughout Birmingham, entitled 9.15.63 (2012), which presents another perspective on the day of the 1963 church bombing. Like the photographic series, the video employs the diptych format. Keller and Sherman describe the video as “using a split screen to underscore similarities and disjunctions between two images: one side shows the view out the window of a car moving through the city, panning across treetops and an impossibly blue sky; the other shows seemingly ordinary objects and locations—lunch counters, barbershops, classrooms—from which African Americans drew sustenance and from where the civil rights movement took root.” The video concludes at the 16th Street Baptist Church. Together, these projects honor lives lost, and confront continued national issues of racism and violence against African Americans.

In 2017, Bey completed Night Coming Tenderly, Black, a series of beautifully rendered and evocative images made in Ohio where the Underground Railroad once operated. As landscapes, these large black-and-white photographs mark a formal departure from the artist’s previous work, though they pose many of the same existential questions. Shot by day but printed as if they were taken at night, in deep shades of black and gray, they explore blackness as color—inspired in part by the photographs of Roy DeCarava—and as race. Named for the final refrain of Langston Hughes’s poem “Dream Variations,” and originally installed at St. John’s Episcopal Church, Cleveland, thought to be a key stop on the Underground Railroad, the series conjures the spatial and sensory experience of a slave’s escape to the North.

Bey’s most recent body of work, In This Here Place (2020), is the third project in Bey’s History series and focuses on plantations in Louisiana. All of the photographs were taken in Louisiana, along the west banks of the Mississippi River and at the Evergreen, Destrehan, Laura, Oak Alley and Whitney plantations. These new, large-scale photographs visualize the landscape and built environment where the relationship between African Americans and America was formed, portraying the sites of the forced labor of enslavement. The series represents a deep witnessing and rich visual description, evoking the traumatic past in now-unpopulated landscapes.

Dawoud Bey: An American Project is at the Brown Foundation Galleries, Beck Building.

More information available at www.mfah.org/dawoudbey.

Photos courtesy of MFAH